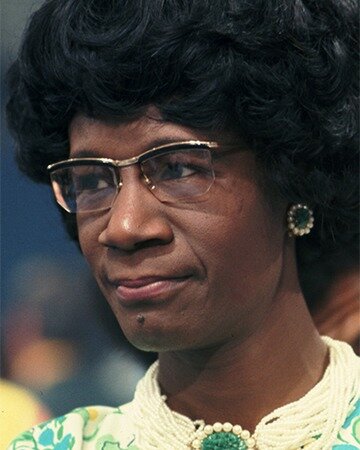

The Honorable

Shirley Anita St. Hill-Chisholm was born one hundred years ago this month, on November 30, 1924, four years after the

19th Amendment to the

U.S. Constitution granted

Women’s Suffrage. She is the first African American to run for a major party’s nomination for President of the United States, and she is the first woman to run for the

Democratic Party’s Presidential Nomination. Her campaign was underfunded as many Americans did not think the country was ready for a Black woman to be president. She said, “I am not the candidate of Black America, although I am Black and proud. I am not the candidate of the women’s movement of this country, although I am a woman and equally proud of that. I am the candidate of the people and my presence before you symbolizes a new era in American political history.”

Recent political events have catapulted American Political History into a new era, a new stratosphere where most people never thought we would land. Launching a presidential campaign in 1972, Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, against great odds of racism and sexism, waged an epic campaign that has gone down in the annals of history as a seminal moment in political activism and feminism that shall forever be hailed as a springboard for women in politics. In 1972, there were only eleven women in Congress; today, there are more than one hundred fifty (CAWP, 2024).

Chisholm was born in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of

Brooklyn, New York, to Charles St. Hill, a factory worker from Guyana, and Ruby Seale-St. Hill, a seamstress from Barbados, immigrated to America seeking the American Dream, searching for better lives for themselves and for their future progeny as they no longer desired to live bound and shackled to the impoverished subsistence of sharecropping (Chisholm, 1970). Struggling with the exorbitant cost of childcare, the St. Hill’s sent their children to live with their maternal grandmother, Emily St. Hill, a sharecropper in Barbados.

The Vauxhall Village of Barbados appeared to be a millennium behind Brooklyn. There was no indoor plumbing, and outhouses stood tall and proud in the backyards. Where the St. Hills lived, the landlord’s crops were also in the backyard, while the front garden consisted of yams, sweet potatoes, pumpkins, cassava, and breadfruit. And there were goats, pigs, chickens, ducks, sheep, and cows (Chisholm, 1970). Whereas just about every child in Bed-Stuy was whisked off to school early in the morning by working parents, without breakfast, then went home for lunch while their parents were still at work, to eat meatless sandwiches, and then later have dinners of processed food, in Barbados, vegetables and fruit were always at the ready and could be grabbed and gobbled on the way down the road. Eggs and milk were also aplenty, and fresh meat was in great supply.

At a very young age, Shirley assured herself that she would one day work to make sure that children in Brooklyn and throughout America would have enough to eat, that they would receive a quality education, and that parents could earn enough money to support their families. She would never in her life forget her early upbringing and the beautiful aroma and atmosphere of the farm. She said, “Years later, I would know what an important gift my parents had given me by seeing to it that I had my early education in the strict, traditional, British-style schools of Barbados. If I speak and write easily now, that early education is the main reason” (Chisholm, 1970, p. 27).

Shirley graduated from an all-girls high school in Brooklyn and from

Brooklyn College, which was free for high school graduates in the borough with high GPAs. In college, she continued her high academic performance, earning a B.A. in Sociology, cum laude. She pledged to the

Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, then went to graduate school and received her master’s degree in Early Childhood Education from

Columbia University. She learned to speak Spanish fluently and was a champion on the debate team in college. Her professors suggested she consider a career in politics, but she did not originally see the feasibility of such a venture, believing that her double handicap of being both Black and female in the turbulent 1940s and 1950s would make such a career a virtual impossibility. Instead, she chose to become an educator and began her career teaching at a daycare Center in Brooklyn from 1946 to 1953 (Chisholm, 1970).

She married Conrad O. Chisholm, a self-employed private investigator who immigrated from Jamaica for the same reasons as Shirley’s parents. They wed in 1949 and lost two babies due to miscarriages. Conrad always wanted a family but knew that Shirley also valued having a career. So they compromised and agreed that they would both work and not focus on bearing children (Chisholm, 1970). In the 1950s, Shirley Chisholm became the director of the

Friend in Need Nursery School, then the director of the

Hamilton-Madison Child Care Center in Lower Manhattan, and then took a position as a consultant with the New York City Division of Day Care, where she supervised ten daycare centers with ten directors, seventy-eight teachers, thirty-eight other employees, and a four hundred thousand dollar budget (Chisholm, 1970).

Chisholm first ventured into politics when her hairdresser introduced her to Wesley “Mac” Holder. A Guyanese-American, Mac was committed to helping Black political candidates win elections in Black communities. Chisholm called him the “shrewdest, toughest, and hardest-working” (Chisholm, 1970, p. 48) political activist in New York City and said that meeting him changed her life. Together, they worked to elect

Lewis S. Flagg, Jr., the first Black judge in Brooklyn, and Thomas Jones, Brooklyn’s second Black Assemblyman. She was a member of the Seventeenth Assembly District Democratic Club, the Bedford-Stuyvesant Political League (BSPL), the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the

Brooklyn Democratic Club, the

League of Women Voters, and the

Unity Democratic Club. When Jones decided to run for a judgeship on the civil court bench in 1964, Shirley Chisholm ran and became a State Assemblywoman. A Black Female, a top political candidate in this country of racism and misogyny who could successfully accomplish a first could demonstrate the worth of women and others from minoritized communities (Chisholm, 1970).

This was a major victory, giving her a position in the

New York State Legislature where she could be the voice of the people living not only in Brooklyn but across the state. She now had political power and could introduce new legislation and have a say in how funds in the state budget were allocated, ensuring financing for New York City school programs and generally making life better for people in her community. In 1968, Shirley Chisholm became the first African American Woman elected to Congress and the first Black Congresswoman from Brooklyn. She faced lots of sexism and racism and was assigned to the

House Agriculture Committee and the Rural Development and Forestry Subcommittee, where it was expected she could have the least impact because there were no farms, rural communities, or forests in Brooklyn. She thought it was a ridiculous assignment and wanted to protest vehemently, choosing instead to be a team player, figuring since “the committee had jurisdiction over food stamp and surplus food programs and is concerned with migrant labor” (Chisholm, 1970, p. 98), she could still make a contribution. It could be inferred that the congressional leader had placed her there because she was a Black woman, and he thought it would be funny to put her somewhere where she could be of no significance. But she also knew that if she failed to make an impact, it would make it harder for every Black woman who came behind her.

Fortunately, Shirley Chisholm knew how to make the best of a bad situation. She learned in life that with every challenge comes a chance to shine. There is no such thing as a problem, only opportunities; every stumbling block is a stepping stone, and every bad situation can be a blessing from God. There were loads of surplus food produced by the agricultural society, so Chisholm used it to feed the poor and the hungry throughout America, Bed-Stuy included. She worked to expand the food-stamp program and led the efforts to create the WIC Program –

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (Hackett, 2023). She was pleased that she was able to help so many poor families have more food to eat. Soon, Chisholm was rewarded and assigned to the

Education and Labor Committee, which greatly aided American schools, particularly Brooklyn and New York City Schools.

Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm also provided great aid to a new generation of politicians, doing so with grace and dignity while dealing with sexism and racism. She received extensive criticism from white people but also from some Blacks. She said, ”They’ve said I like whitey, that I’m too close to Hispanics, that I’m not black enough . . . I resent people evaluating me on the superficial manifestations of my behavior. Why don’t they ask me to explain?” (Perlez, 1982)

Chisholm explained to her many proteges that they should never relent but remain assiduous in their assent to serve the people. Like many others with formal education, she had received many years of training and guidance in history, philosophy, and psychology, and in her work with grassroots organizations, she had participated in countless political activities to foster change. And all the while, she mentored young people to carry on the fight just like Holder and Jones mentored her. All this was intended to prepare young adults who could see all sides of an issue and act for the greatest good. Chisholm mentored scores of young women who volunteered to work on her campaign, and she hired some of them to work in her office.

Her political career provides the paradigm for the repudiation of puerile pundits and putrid politicians who have the audacity to deny the citizenship of certain Black candidates and deny their racial heritage by claiming they recently turned Black to gain a political advantage. When he presented Chisholm with the

Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously on November 24, 2015,

President Barack Obama said, “Shirley Chisholm’s example transcends her life. When asked how she’d like to be remembered, she had an answer: “I’d like them to say that Shirley Chisholm had guts.” And I’m proud to say it: Shirley Chisholm had guts” (Obama, 2015).

She had guts, and she paved the way for many young Black girls to see themselves as congresswomen, senators, and even president. Shirley Chisholm mentored

Congresswoman Barbara Lee from California, who has served since 1988, and Barbara Lee mentored a young woman from her home state named

Kamala Harris, who said, “Shirley Chisholm created a path for me and for so many others. Today, I’m thinking about her inspirational words: ‘I am, and always will be a catalyst for change’” (Harris, 2021). As The Star goes to print, it is evident that at least half of all Americans are convinced that America is, in fact, ready for a Black female president.

Works Cited

CAWP (2024). Center for American Women and Politics. Rutgers-New Brunswick. Eagleton

Institute of Politics. https://cawp.rutgers.edu/facts/levels-office/congress/history-women-us-congress

Chisholm, S. (1969). Shirley Chisholm, Unbought and Unbossed. Amistad/HarperCollins.

New York

Harris, K. (2021). U.S. Senator Kamala Harris (Archive). Facebook.

https://www.facebook.com/share/p/hE11guPYSXJuxFXW/?mibextid=oFDknk

Obama, B. (2015). The White House Office of the Press Secretary. Remarks by The President

at Medal of Freedom Ceremony. 24 November 2015.

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/11/24/remarks-president-medal-freedom-ceremony

Perlez, J. (1982). New York Times. Rep. Chisholm’s Angry Farewell. 12 October 1982.

https://www.nytimes.com/1982/10/12/us/rep-chisholm-s-angry-farewell.html